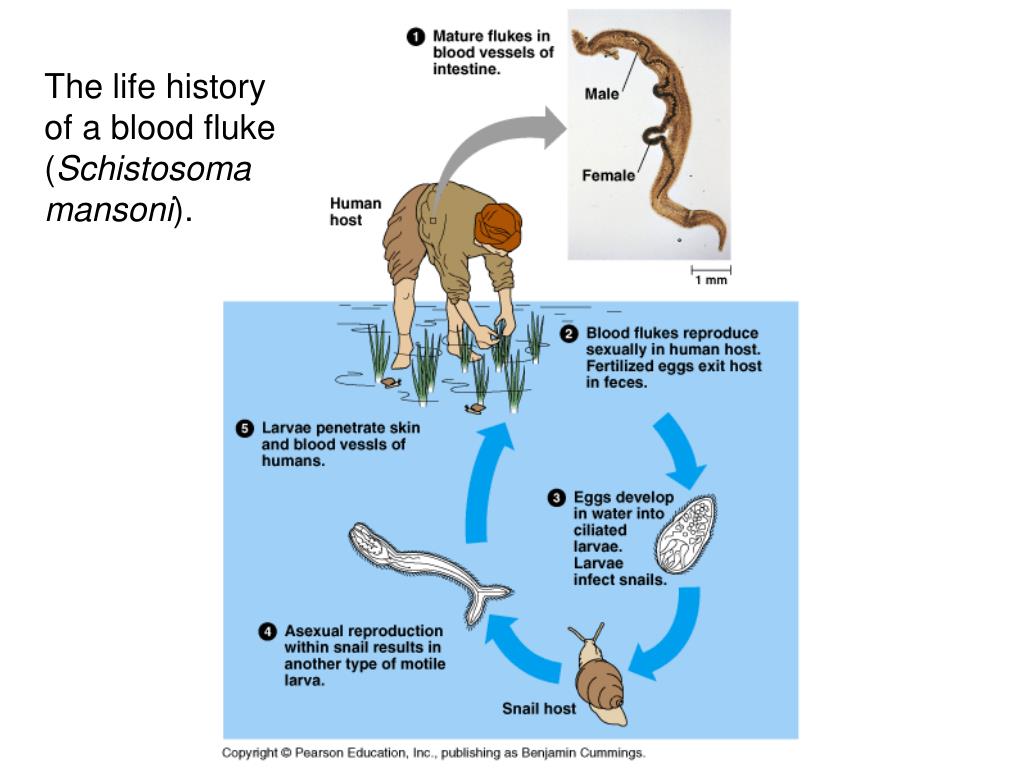

These fruit bats, natural hosts for Nipah and other henipaviruses, had sufficient contact with the pig farms to allow the virus pathogen to “spill over” from the wildlife reservoir into the domestic pig population, causing mortality for pigs and humans (and cats) in contact with them. For example, Nipah virus emerged as a deadly pathogen in Malaysia when pig farms were built close to forest areas frequented by fruit bats ( Figure 9-1Īnd Color Plate 9-1). For many zoonotic diseases, however, such approaches are limited because the ultimate causes of infection in the animals may not be addressed sufficiently. The control of such “us versus them” diseases has traditionally involved measures such as control of the animal reservoir (through culling, quarantine, or vaccination) or vector control (through pesticides and personal protection). The problem is viewed as an infectious animal reservoir that then poses an infectious risk to humans-either through direct contact with infected animals and their excretions, meat, milk, or other tissues, or via a vector transmission bringing the pathogen from the animal population into human hosts. One possible reason is that the traditional approach of the human health community to zoonotic disease has been an “us versus them” approach.

Therefore the control and prevention of these diseases can be accomplished only through improving approaches to reducing disease transmission among humans and other animals.ĭespite the great deal of attention that has been focused on emerging infectious zoonotic diseases, including severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), West Nile virus, monkeypox, and avian influenza, there has been less discussion and effort targeted at the environmental “drivers” of such diseases. In fact, the majority of “emerging” infectious diseases in the past three decades are zoonotic.

The history of contact between animals and humans has always involved infectious diseases, and today more than half of the infectious diseases of humans are zoonotic in origin. INFECTIOUS DISEASES IN HUMANS AND OTHER ANIMALS: FROM “US VERSUS THEM” TO “SHARED RISK”

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)